Beautiful trailer filmed and edited by Alana McNeill, with audio by John Norman. Featuring Elizabeth Whitbread.

Catch us at Toronto Fringe July 5-15 and Winnipeg Fringe July 19-30.

Beautiful trailer filmed and edited by Alana McNeill, with audio by John Norman. Featuring Elizabeth Whitbread.

Catch us at Toronto Fringe July 5-15 and Winnipeg Fringe July 19-30.

Liz Whitbred, photo & editing by Kendra Jones

How does one approach a text as dense, poetic, emotionally charged, and seemingly disjointed as 4.48 Psychosis? There is an energy seething through the text, and it would be very easy to rest on cliche or the first impression of the play. Sure, it is about a person experiencing psychotic episodes, but that feels entirely simplistic. What drives this person to act? What has sparked these experiences and thoughts? Most importantly, how can an actor justify an act which is so inconceivable to anyone not in a suicidal state?

My wonderful collaborator, Liz Whitbred, and I began to meet back in April. We met once or twice a week, simply to read and talk about the play. At times, our sound designer, John Norman joined us as well. The goal of these sessions was to start from a purely academic standpoint, to unearth what exactly is going on in this play. This would enable us to approach it on its own terms, without imposition. It was a tough go at first, with more questions than answers, but as we continued reading, and discussing, questioning and analyzing, the clear story of this individual's experiences came to life, and the narrative of the play became apparent. That isn't to say that I think we've discovered the "Right" way to tell this story, but we have found a way that speaks to us, and that we hope will speak to audiences.

So, since April, we have primarily met sitting down, reading the words of the play, and really allowing the thoughts to inhabit Liz' mind and body. We embark Sunday on creating the physical and choreographed landscape of the play, which we've almost entirely avoided to this point. Our highly academic approach may seem unusual (and counter to what many other directors may do) however in order to make sense of the text, and ensure no imposition, we felt it useful. Once analysis was done, we simply read the script over and over again, and began replacing live voices with those which would be recorded. We tried reading in public spaces and private ones, which really called to light moments in the text where she is crossing a line, and often when she is choosing to do so.

And now, we will create the physical score and add it all together. We have the voices recorded, and the brilliant John Norman is piecing the final audio score together for us while we create the physical score.

More to come as we begin to sew the pieces together!

My essay Re-Imagining Expectation for the Theatrical Experience is a part of this great collection of essays on contemporary immersive theatre practices, published by Common Ground Publishing, and edited by Josh Machamer. My essay touches on formative experiences and experiments in my own exploration of immersive theatre work, including work created in London, UK and in Winnipeg, Canada.

Abstract

Re-Imagining Expectation for the Theatrical Event examines contemporary practices of immersive theatre and their efficacy in relationship to audience expectation for the what and how of the theatrical event. Contrary to earlier forms of theatrical performance, immersive work takes on many characteristics in terms of the dramatic versus the theatrical, the role of the audience in the creation of the experience, and the role of the performer in preparing and guiding this experience. At its heart, immersive theatre calls upon both performer and audience to connect, and to re-define their understanding not only of what makes the theatrical event, but what agency they have in the events taking place in front of them. This chapter combines an examination of the work of impel Theatre in Canada with the formative experiences Artistic Director Kendra Jones had performing in immersive work in London, UK for Run Riot’s You Me Bum Bum Train and RADA Festival’s How We Met. Throughout, the chapter seeks to demonstrate the necessity of such a theatrical evolution in the current milieu to ensure the continuance of the art form in an increasingly digitally connected and personally disconnected world. Kendra Jones is an independent theatre director, writer, and academic based in Toronto, Canada, and artistic director of impel Theatre. She has previously taught at the University of Winnipeg Department of Theatre & Film, and Prairie Theatre Exchange School.

About the collection:

Immersive Theatre: Engaging the Audience is a collection of essays that look to catalogue the popularization of “immersive” theatre/performance throughout the world; focusing on reviews of works, investigations into specific companies and practices, and the scholarship behind the “role” an audience plays when they are no longer bystanders but integral participants within production. Given the success of companies like Punchdrunk, Dream Think Speak, and Third Rail Projects, as current examples, immersive theatre plays a vital role in defining the theatrical canon for the twenty-first century. Its relatively “modern” and new status makes a collection like this ripe for conversation, inquiry, and discovery in a variety of ways. These immersive experiences engage the academy of “the community” at large, going beyond showcasing prototypical theatre artists. They embrace the collaborative necessity of society and art–helping to define the “stories” we tell and the WAY in which we tell them.

You can buy a hardcover or PDF copy here: https://cgscholar.com/bookstore/works/immersive-theatre

Found behind Library Street Collective, Detroit.

A recently released study has indicated that almost 70% of students entering Toronto's public art-focused high schools identify as white, and predominantly come from wealthier households, which as you can imagine, has called into question not only the admissions process, but the courses themselves. I don't think that it takes a lot of inquiry to identify the root causes of this problem: first, accessibility to the key genres of art that are assessed in the admissions process, and second, accessibility (and reality) of the ability to create and sustain a career in the arts if you do not come from a position of privilege.

Lets deal with the first point; what is taught. Art schools tend to admit students who have a pre-identified strength in an area, whether it be music, dance, visual art, and the criteria for these strengths lends itself to favour those who have had some kind of training. How, for example, could someone with no formal training in dance walk comfortably into an audition and succeed? It would be only those students who hold a particularly adept natural skill, and a significant amount of courage or self confidence. Thus as you can imagine, the first obstacle of having the courage is then met by the second obstacle of appropriate preparation, which then, if those hurdles are cleared, there is, of course, standing out in a room full of skilled and at least partially trained performers. Is it any wonder that the admitted students skew toward higher income households, where they are more likely to have access to training? When siting across that table as an audition panel, how much are we looking for a partially moulded pre-trained package, versus someone whose talent is raw and untouched, but will need a lot of work? It is so easy to default to those who already have some of the skills as a baseline, rather than give the public school opportunity to the kid who wouldn't otherwise afford to get music or dance or art lessons?

Even if we look past those hurdles, and wipe that clean, interest in those more traditional fields is an issue; if someone is a street artist, is their work going to be accepted or valued the same? What about someone who can't play piano or violin, but can work a TR8 like no one's business, and can compose music like you've never heard before? Or what about someone whose work is multidisciplinary? This is often something that even as adults is just beginning to be valued and encouraged, so is it being encouraged amongst middle schoolers applying to these stringent application criteria?

This in part leads us to the second point: feasibility. I grew up in a family where a career in the arts was something of a pipe dream, and where my own growth, education, and access was slowed by the fact that I couldn't simply afford to do free apprenticeships, volunteer my time, or go on a tour for months for a couple thousand dollars. When you grow up in a space where there are few working artists around you, and where there is no safety net enabling you to "focus only on your art" and not have a backup, your ability to develop as an artist, to take advantage of all the "emerging artist" platforms that might require you not to work another job or to fly to another city (on your own dime) are just not open to you. So if you're 13 years old, and looking at your future....does this seem reasonable? And as a parent of a 13 year old, no matter how much talent or how big the dreams of your child are, won't you want them to have something more reliable and steady that can ensure they are fed and clothed and safe as they enter adulthood? How likely are you to encourage this career path, starting at a specialized high school?

We need to do more for kids. We need to provide better public school art education from very early on. I can directly associate my own perserverence as an artist (and success, if you can call it that) to a few early connections I made. I had an amazing music teacher in elementary school, and then had an amazing opportunity to create a brand new musical whilst still in primary school with professional artists who had just come from Ukraine. As I got older, I was lucky enough to get dance training, but even that was at a huge cost to my parents who were working non stop to give us those opportunities. I recognize the good fortune and privilege I have had in that regard, and also acknowledge that it was a lot less than those around me.

We cannot allow young artists with something to say to be silenced simply due to access, and pretend to call our system "public" education. The admissions process as well as the content of courses requires serious examination to ensure the continued validity of these programs. Their necessity doesn't need proving.

"No one ever asked me to take my arm down."

My Arm is the first play Crouch wrote, and it is filled with a sense of playfulness that is difficult to articulate. Told by one performer (Crouch) with the aid of every day objects collected from the audience, and the use of a doll, and a video camera, My Arm follows the story of a young boy whose determination sets the course of his life. Always speaking in the first person, it is the source of some enjoyable humour when the character's described actions or appearance are so clearly at odds with the performer we see in front of us.

Crouch's choice to not "act" but rather "tell" the story renders the piece far more theatrical than it would be were the same story realized through traditional theatrical "embodiment". Yet Crouch tells the story with more intense focus and "liveness" (that much debated concept in Toronto theatres these days) than most other actors I can think of in recent memory.

The play itself raises a multitude of questions about ethics in art. Of course, demanding we ask ourselves what is art versus artifice (or scam?), but also when the characters in the story begin marking art, it demands questions of responsibility and ethics in relationship to a subject. When representing someone in your work without their knowledge, when drawing them or representing their "story" in your work, when offering the subject funds for their representation when it is clear no other choice is feasible, and even further, the ethics of responsibility to a child or loved one. This is all juxtaposed with the careful and specific manner in which Crouch requests objects from the audience to use in the performance, both in his spoken text, and in the program note.

Crouch is a masterful storyteller, managing immense pauses, improvised object theatre, all while keeping the audience utterly captivated while he plays with these ideas and our imaginations.

I have many more thoughts on this piece, and will soon share them.

Robert Lepage in 887

It has taken me a little while to write about this show, in part because I was wondering whether the feeling of awe would subside; whether I might come to a point in my reflections on the play where is began to see cracks in the surface. Alas, a week on, and there are none.

Lepage is a master storyteller, completely in control of the simplicity of the story and his means of telling it at all times. Starting out speaking colloquially, he slips into the world of the play so seamlessly that once the audience realize, there is a collective gasp -- upon the first reveal of the set. We spiral into the world with him, one of memory and recollection, wherein he parallels his own childhood memories of people, most importantly his father, with a story of his own desire to be remembered in a certain way.

Lepage's ingenious set design makes use of his love of live video in a striking way, illuminating the spaces he is talking about on a physical space with life -- causing us to ponder the simultaneously static and living nature of our memories of people. They remain the same, and yet change, almost unknown to us. Along with this, his use of perspective helps further this story of how we perceive and therefore how we remember. Lepage, the adult reflecting backward looms large over the apartment building, while Lepage the small child in the memory is towered over by the image of the soldier, brilliantly realized through camera angle and its relationship to a pair of boots.

Despite all of the stage magic and technology, every moment, every image comes across as completely simple and effortless. Even the use of smell, moving from a moment with firecrackers in a metal bin, to rolling in boxes of memories seems almost accidental. But rest assured, not a single thing that transpired on the stage was accidental, each moment carefully planned and yet seeming to be a surprise even to Lepage himself.

Another layer, of course, is the inherently Canadian story Lepage tells, weaving between French and English, manifesting the conflict of the play through nothing smaller than the French/English conflict present even today in Canada, and most certainly in 1960's Quebec. Through the use of Michèle Lalonde's Speak White, a stunning climactic moment in the performance by Lepage, every anxiety and inadequacy of "canadian-ness" came to light; particularly poignant in the face of the Canada 150 celebrations. What version of Canada are we celebrating?

I'm truly honoured to have seen not only this master's work, but performed by the master himself. This will not soon leave my memory.

Photo: Sam Polzon

Apologies for sharing thoughts after this one has closed.

The Seer starts with an image of desolation; a woman and a man are attached to one another by a rope, both tattered and appearing worn down. It takes a moment to adjust, in the darkness, as we hear 3 voices, but see only two forms. All becomes clear momentarily, although the gift of this piece is that it rarely explains, but rather lets you surmise on your own. Director Chantel Martin uses this unconventional space well, situating a variety of locations at different physical areas of the open room, allowing the audience to move where they feel they'd like to. Standing throughout the 60 minute piece, this enables the audience to feel a bit of the same exhaustion the characters are feeling, serving to engage us further.

At times the story was reminiscent of Caryl Churchill's Far Away, with its almost episodic nature and lack of explanation. The three characters are related, but we don't know how, or why, and are desperate to learn. It did run the risk of dragging, but again, this was cleverly avoided by Martin's inventive staging and use of immersive theatre techniques. The space itself became a character in telling us a part of the story.

It is less common than you'd think to see a piece of new Canadian writing that is as highly stylized as Sean Dixon's The Orange Dot. Borrowing a structure from Beckett's Waiting For Godot and Ionesco's The Lesson, Dixon has created a world which is not as it seems, in which inane conversation and repetition, two classic absurdist techniques, are made to seem normal, until suddenly they aren't. Discussions of pop culture and daily city life, the back and forth banter of Joe and Nat, seem like an inane play at first, leaving the audience wondering why they are bothering, and yet we stay, we watch. Slowly the world starts to crumble, and the inane begins to be more clear, but by time we realize it is happening, things are well off course and deep into the absurd.

That is the thing that is most difficult about the absurdist style. How can the shifts away from normalcy be clear and concise, and yet not telegraph to the audience what lies ahead? This debut production, directed by Vikki Anderson, struggles somewhat with those shifts. The early shifts out of the recognizable world and into the absurd were less clear in my view, than they ought to have been; rather than causing the audience to begin to question what they are watching, they served to contribute to confusion. It is a delicate balance to manifest the verfremmdungseffekt I believe is central to achieving this in a production, and at least in the performance I saw, it wasn't quite there.

That said, overall the performances from Shawn Doyle and Daniela Vlaskalic were quite good, with Doyle standing out until the final moments when Vlaskalic came into her full and truthful range. Earlier scenes didn't always link up from a stylistic perspective, with Vlaskalic putting on a folksy overdrawn accent that she shifted in and out of throughout scenes. Again, I think this comes down to clarify of the shifts in the world of the play; some finer subtlety in these shifts would have helped to enable the audience to think about the play and the message more clearly, rather than simply wonder what was going on in these moments.

Definitely a script worth seeing, and the difficulties i list above are likely to be worked out through continued performance as the production settles into itself later in the run.

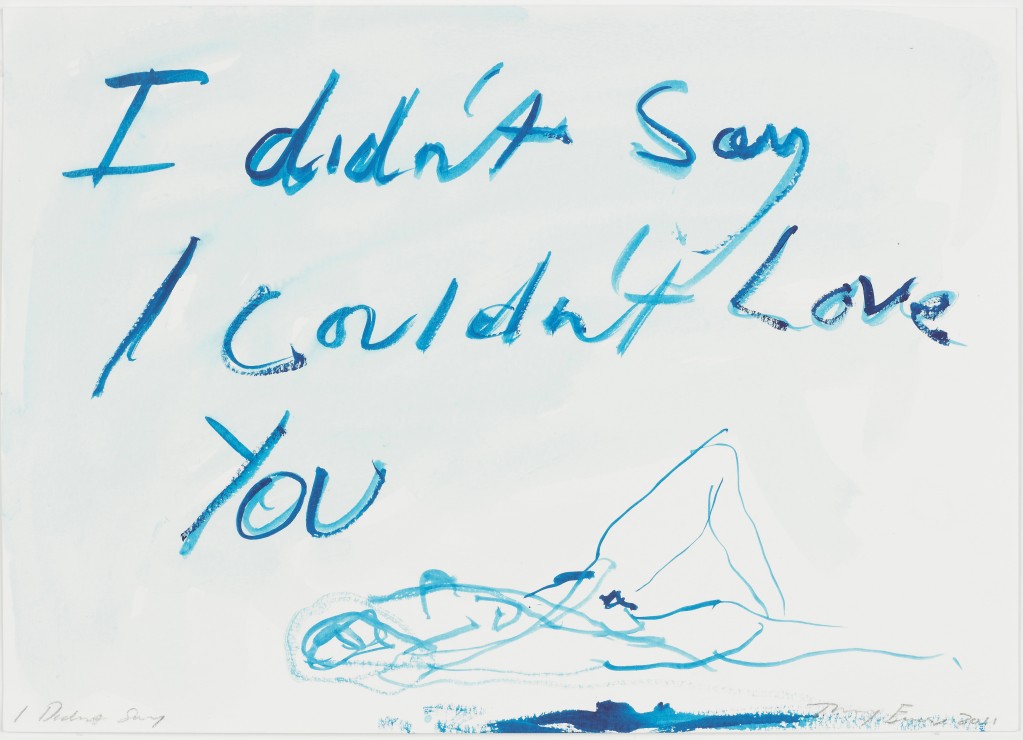

Tracey Emin - I Didn't Say I Couldn't Love You

Every director has plays that sit on their bucket list, and for a lot of them, that's all that will ever come of them. Your bucket list plays are filled with scrapes of ideas and images for what you would do, but they are never fully realized. But then, the times comes where you get an AD to agree to giving you the chance. Then you get the rights. And then your stomach flips....now I have to do it.

I've had that series of experiences this spring, when one of my long-time bucket list plays, 4.48 Psychosis by the enigmatic and irreconcilable genius, Sarah Kane, came my way. From my very first read of the play, I was captivated. On the surface, the play makes next to no sense; it feels like a long form collage poem of beautifully dark statements that challenge your sense of remaining light in the world, interspersed with scenes. Or are they scenes? There are no indications of the number of performers, the number of voices, the ages or genders. Just words. And thoughts. And somehow, it is hopeful.

So, I embark upon my new Everest. I have an amazing team lined up. I'm directing for Theatre By The River, with the wonderful support of our company members and AD. I have the honour of working with the shining and adventurous young talent, Liz Whitbred on stage. And I get to return to audio collaboration with my partner in life and art, John Norman, who will help Liz and I transform her singular presence in space and time using sound.

I'm unbelievably excited to direct what I hope will be my most radical experiment yet. Part play production, part sound installation, part poem. You can trust it will be something different, and I hope you'll come on the journey with us, both here on my blog (where you can expect updates, rants, and of course shameless self-promotion) and when we perform it in The Toronto Fringe Festival and Winnipeg Fringe Theatre Festival this July.

Until then...

street art, found in Williamsburg, NY (2016)

Walking through the bowels of Dundas station, early on a Tuesday morning. The man sits, legs crossed, at the edge of the stairs. People pass by. He talks to them. It mostly makes no sense, and they mostly walk by. Ignoring him.

She looks his direction, catches his eye. She smiles. He is a human, a person, after all.

"Ah, she knows what it means to paint herself in black". This pierces through the space as morning commuters rush by.

This sits with her for the rest of the day. It feels like a compliment. But she's not sure why.

Tom Rooney & Moya O'Connell in The Wedding Party

It has taken me awhile to feel like I could write about this play. The Wedding Party is deliciously fun, tears in your eyes, gut-hurt funny. This isn't the reason it took me so long. In the days following my attendance at this hilarious, intelligent, beautifully written and expertly performed production, it felt as though the world was falling apart. Trump began a daily barrage of executive orders that upended what we think about human decency and caring for others. In the face of this, how could I reconcile a play that was by contrast, seemingly so light in subject and tone?

It came to me the other night, however, on one of my late night dog-walks, seeing people come out of the theatre with huge smiles on their faces (I live upstairs of The Crowsnest). Seeing those faces of pure joy as they walked toward their cars or transit. Hearing them recalling favourite moments, that they'll "never look at a dog in the same way" or "windbreaker of lies" followed by shared laughter, it occurred to me that the point of this kind of play is to be a release. A release from the drudgery, the sadness, the despair. And it is so utterly necessary sometimes to just laugh. To laugh at the idiosyncrasies of an elderly grandmother, or a young boy, or hilarious twin brothers with opposing personalities. To laugh when we see ourselves, our own humanity in these people.

This post is less about the production (which is fantastic, and I 100% recommend to anyone, anywhere) but rather about why this sort of play, which might feel frivolous in these times, is still important. We still need to laugh. To laugh is to remind us of our humanity.

Also, seeing Tom Rooney in a scene with himself is something that everyone should experience.

I went in knowing next to nothing about the production, and from the first moments was captivated. Telling the story of Henry VIII's last wife, Catherine Parr, and her relationship with the King, her lover, and the King's children, it takes a starkly modern view of language and relationship. Though the source material is history, the script is incredibly modern, filled to the brim with razor sharp wit and deep truth about the complexities of love.

Maev Beaty is sublime as Parr, who is every bit the intellectual equal (if not superior) to the King. She faces off against Joseph Ziegler's Henry, who is infuriating and tempestuous, yet also kind when he chooses to be. The three children are delightfully modern - as the gothic older teen, Sara Farb oozes acidic disdain for the adults around her, while Bahia Watson is charming as the younger Elizabeth, sweet and innocent, but increasingly wise to the challenges presented to her by her gender and position.

The design must be mentioned here as well; the modular and very simple steps transform into multiple spaces with ease, and the costumes each hold a visual reference both to pop culture, and to their historical counterpart. The lighting complimented this beautifully, and served to underscore the importance of characters in the story.

Hennig's script creates 6 challenging characters, and 3 incredible women that are a gift to actors. It isn't often you come across a new play that holds such an inherent timelessness in its understanding of relationships and power. This play needs to be on the reading lists for every University's theatre courses in Canada. Now.

The Lion In Winter is a darkly comic re-imagining of the story of King Henry II and his wife, Eleanor of Aquitane in their epic battle of wills. Their machinations use their children as chess pieces, always vying for power through the manipulation or tricking of one or another. Krista Jackson's production takes a scene or so to warm up, however once the cast settle in to the quick pace it begins to crackle with energy. The actors are extremely well cast -- of particular note is the delightfully cunning Brenda Robins as Eleanor. With so many twists and turns, the script would almost be exhausting, however Robins deft turns in energy and objective keep it from growing stale. Sarah Afful is also notable as Alais, who in the hands of a lesser actor would come across as melodramatic.

The one piece that remains puzzling is the design; featuring three pillars to create multiple rooms and space, they are covered in a spackled black paint which does not align with the richness of some of the costumes, nor does it quite contrast fully. Similarly, the overall look of the costuming lacks a cohesive voice and sense of style, resulting in looking a bit thrown together.

I'm extremely excited to share that my audio installation Autel has been selected to be a part of the annual Festival of Original Theatre (FOOT) at the University of Toronto's Drama Centre which runs Feb 2-5. This is the 25th anniversary of the conference, coinciding with the 50th anniversary of the Drama Centre @ U of T.

This year's theme is "Sounding The Inner Ear of Performance" so my Autel piece, which I first showed at RADA in London, and subsequently at the Gas Station Arts Centre in Winnipeg is a great fit.

So much of my own directing and creative work has focused on the power of sound as an active character in the theatrical experience, and I am honoured to have my work included among these amazing thinkers and creators.

For more about the conference (you can still register) check out their website.

More about Autel:

Autel is a performance installation piece first shown at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art in London, March 2012, and subsequently shown at the Gas Station Arts Centre in Winnipeg from October to December 2012. It invites the viewer to experience their own ritual of identity, and examine this mask as they look at others, also performing a ritual of identity. The viewer should, after the experience, begin to question the authenticity of their own public identity, and those they encounter, along with the authenticity of the experiences they have for the remainder of the performances. What are they seeing? How are they responding? Are they responding in a specific way that they believe is correct, or that is for the benefit of others?

Inspired by the work of playwright Jean Genet and composed of a collage of his words and those of Antonin Artaud, Autel is an auditory experience which challenges social constructs of identity and the way we interact with art.

I'm extremely excited to share that I will be directing a new play by Crystal Wood called Grief Circus for commonplacetheatre's 2017 season, which marks the company's Toronto debut.

I'm particularly excited, as I had the great pleasure of directing a short reading of Grief Circus a few years ago for Sarasvati FemFest. I loved the script then, and was thrilled to be offered to direct a full production now.

We are holding auditions for all 3 plays that make up the season on Jan 14, 15, 16.

For Grief Circus specifically, I am looking to cast the following roles. Actors of all backgrounds are encouraged to audition.

Leah - female, plays 15-20

Jessie - female, plays 17-20

Carol - female, plays mid 40's

Charlie - male, 21

Reporter - male, 40's

For more about commonplacetheatre, the season, and to book your time visit their website.

17 years on from their last play, and an ocean of encounters in between, Tina and Bobby are back. Meeting in their park, their latest encounter has a spark underlying waiting to ignite from the very moment. The sense that the pair aren't comfortable together, but can't bear to be apart lurks beneath their conversations as little drips of their history and what transpired in these 17 years come to us.

Under Ken Gass' direction, the story ebbs and flows beautifully as the pair race into their united truths, then throw on the breaks, only to find themselves racing again. The taut timing Gass elicits from the script speaks to his inherent understanding of Walker's style. The piece is superbly performed by Wes Berger and Sarah Murphy-Dyson; at first, Berger's Bobby feels a bit stiff, however as the play runs forward, we see that this stiffness was intentional, as he remains guarded against the truth that neither will speak. Murphy-Dyson offers a powerhouse performance, demonstrating an immense specificity in what might in a lesser actor edge toward melodrama. The pair spar verbally and at times physically with great intensity and nuance for the 75 minute script.

My only qualm would be that Walker gives us just a touch too much exposition, particularly related to people we don't see. The true strength of the script is that it is just two people, doing things to one another incessantly, both intentionally and unintentionally; and we don't need anything else.

The Damage Done runs until Dec 11 at Canadian Rep Theatre.

As a lover of theatre, I have to admit that I have mixed feelings about verbatim plays. On one hand, I find they are an amazing way to explore contemporary and political stories that feels real and connected, unlike purely dramatic fiction which can come across as issue-based, single-sided, and staid. On the other hand, I struggle with issues of ethics in the story (eg: including the conversation where someone asked not to be included, or highlighting as a plot point the refusal of those with opposing opinions to participate). That said, I found Soutar's script to deftly avoid many of these potential roadblocks, to create a fast-paced and engaging story about something extremely important -- water.

The performers of this re-mounted production were uniformly outstanding, most of whom played multiple tracks of parts with quick change timings that would make a stage manager faint. Juliet Fox's outstanding modular set demonstrated both utility, and an overwhelming sense of the fragility of our current situation portrayed through the play, by situating the actors on a set completely constructed of pallets.

There were definitely bumpy moments for me, from a dramaturgical perspective, including the inclusion of former Prime Minister Harper as a character (though great comic relief) and quite a lot of same-idea pushing businesspeople and politicians -- I felt the script might have benefited from a tightening to focus on what I found the most compelling, the story of the 3 little girls. Hearing the interview questions asked of adults "just doing their job" from the mouths of intelligent young children was jarring, and demanded we pay attention to what and how we answer. An excellent production and script overall, I just felt that this broadening of scope potentially missed the opportunity to really hit home by asking us real and difficult questions. Most adults have been in that position -- where a young person you love and care for asks you a question about something that even you don't understand in the world. When this happens, we are compelled to answer and yet know that there are no words that can answer their unending "why". This was the power of The Watershed, in my opinion. Young voices asking WHY.

The Watershed runs to Oct 30 at Tarragon in association with Crow's Theatre & Porte Parole.

Photo by Kendra Jones

Unlike a lot of solo shows one expects to find at a gallery of the reputation of the AGO, the work of Theaster Gates is considerably more ephemeral, more disruptive, more inherently political. In asking his question, "how do we determine whose house to commemorate" and conflating this with the House Music movement, Gates demands that the viewer acknowledge our own limited purview of who "deserves" to be recognized.

Upon entering the main space, the music (which is at a quite loud volume) pierces the air, and draws you toward the Reel House, a tribute to Chicago musician and pioneer Frankie Knuckles. The joyful and energetic music creates a safe space, one where it is okay to relax and engage personally with the artwork, and contrary to many much more sterile and silent gallery experiences.

Surrounding the Reel House are several canvases with geometric shapes in primary colours. At first glance they appear to reference modernist painting, however upon further view into other rooms, you learn that these are visual representations of scientific charts which show statistics of black households in the period surrounding emancipation. Progress is the key underlying message, and this meters our response to Gates' initial question.

The final space, Progress Palace, is the culmination of these ideals. It is a separated room to enter, where a new group of sounds fill the darkened, purple-lit space. The large physical installation Houseberg creates fascinating reflection patterns on the wall as it turns slowly. The projected images cycle in tandem with the music which emanates from a skeleton of a DJ booth, playing the video House Heads Liberation Training, with dancers and singers in un-practiced sound and movement. This deconstruction of a nightclub space is wonderful to experience solo -- the absence of other people in the space highlights the potential that occurs when these forms intersect. The theatrical nature of the potential within this constructed (or deconstructed?) space is captivating.

Gates exhibition as a whole is absolutely work seeing -- runs until October 30th at the AGO.

Forced Entertainment - Complete Works: Table Top Shakespeare, Richard II

UK company Forced Entertainment have, in recent years, leveraged technology far more creatively than many companies, and with a populist twist. Rather than the flashy (and pricey!) live stream performances to Cineplexes around the world a la West End and NT Productions, Forced have been providing their performances via free of charge live stream. This, of course, works fittingly with the durational nature of their work -- I can't imagine a Cineplex giving up 24 hours in one of their cinemas. But the result is that this highly unique work can make its way to North American audiences. The feed of their Complete Works -- a Table Top storytelling performance of the Complete Works of Shakespeare -- is available until September 9th streaming from TheaterFestival Basel in Switzerland at this link.

So...what is it? Well, lets delve in to their Richard II for a sampling. Told with a single performer in a storytelling format, Richard II employs the use of every day objects one might find at a bar to create the characters of the story of the ineffective English King who gave up his throne to Henry Bollingbroke. It sounds, in premise, silly -- how can a bottle of Ballantyne's represent an English King? How can tiny salt shakers represent his ill advised friends, Bushy, Baggot, and Greene? Well in the hands of a truly captivating storyteller, able to whittle down the story to the key plot points and perspectives while imbuing these seemingly arbitrary objects with the emotions of the story, it is truly successful.

The objects begin feeling ordinary, but quickly enjoy significance. It is a demonstration of the power of semiotics in storytelling -- that objects we present on stage are steeped with meaning because we GIVE them meaning simply by touching them in this lit space. And the objects take on the power of the story so beautifully that by time the play ends, and Bollingbroke stands over Richard's body -- one alcohol bottle standing up, the other tipped over -- we feel the tragedy of this fallen King with such force, almost more so than we would seeing actors on a stage.

I STRONGLY recommend trying one out over the next few days.

Tim Campbell and Sarah Afful in All My Sons

The recent conversion of the Tom Patterson theatre to an in the round venue was perhaps the most perfect decision to frame this outstanding production of Miller's All My Sons, directed by the inimitable Martha Henry. The logistics of the playing space are such that the audience feel situated just over the next fence, or peering in from a nearby treehouse on this neighbourhood, the effect of which is to create an intimacy with the characters which might be lost in a larger and more traditional proscenium space. What is most notable, however, is the mindful pace with which the story progresses; never feeling slow, the story seeps like air slowly leaving a tire, until suddenly it is all out, and crisis hits.

Lucy Peacock delivers a heartbreaking performance as Mother (Kate) Keller, her every choice so beautifully and naturally evoked that one forgets for a moment you are watching an actor, and not just peering in on real life. She is holds the cast rooted, and around her the ensemble weave a spellbinding picture of this neighbourhood and these people. Of particular note are Tim Campbell and Sarah Afful, who take the roles of the young lovers to a new height. With such nuanced performances, I can't wait to see each of them continue to grow as performers and take on more roles.

Absolutely stunning work. The 3 acts flew by, and left us winded, gasping for air. Please see this play.